Gallery

This gallery serves as a virtual exhibition space for images, objects, Sounds and spaces that articulate the stories (or gesture to the untold and undocumented stories) of women in the Haitian Revolution. It combines historical artefacts with contemporary artworks (both visual and expressive) in an effort to show the continuing force, circularity and diasporic mobility of revolutionary stories as well as their historic roots.

![Coloured print of Sans Souci, the palace of Henry Christophe. From: Henri Christophe, King of Haiti. Copie de lettres [manuscript] 1805-6 [FCO Historical Collection FOL. F1924 HEN].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5dc48c2931eef72b776e6581/1599141476622-LYH2200BYS99BEZNCM5I/FCO+Historical+Collection+FOL+F1924+HEN+King%27s+College+London.jpg)

Images

Patricia Brintle is a Haitian-born artist who is now resident in Whitestone, NY. This painting, depicting the purported ‘god-daughter’ of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the nurse and seamstress Catherine Flon, forms part of a series of acrylic paintings by Brintle articulating the stories of Haitian women revolutionaries. Brintle’s caption reads as follows:

Catherine Flon was a seamstress and the god-daughter of Jean Jacques Dessalines, the leader of the Haitian revolution. During the Congress of Arcahaie (May 14 to May 18, 1803) in the town of Arcahaie, two essential points were agreed upon by Dessalines and Petion, the two principal leaders of Haiti at that time: The establishment of a revolutionary army under the supreme authority of Dessalines and the adoption of a flag for that army. On the last day of the Congress, May 18, 1803, Dessalines removed the white band from the French flag and gave the remaining blue and red portions to Catherine Flon who sewed them and turned the bands to their side. The Haitian flag was born. Once it was sewn, the generals of the Haitian Revolution solemnly swore a pledge of allegiance to liberty or death on the flag. This oath was to lead the slaves to victory and freedom. That pledge is called the Oath of the Ancestors. Since then, May 18 has been observed as the Haitian Flag Day. It is a major national holiday and an occasion for parades, marches and pageants. Catherine Flon is regarded as one of the great heroines of the Haitian revolution and independence. In this artwork, the artist depicts the moment when, a year after the creation of the flag, Petion sought the help of Catherine to sew the arms of the republic on the bicolor.

This painting, from Patricia Brintle’s series on Haitian revolutionary women, depicts Marie-Jeanne Lamartinière (thought to have been the companion of Louis Daure Lamartinière) who is recounted as having fought among the troops during the conclusive revolutionary battle at Crête-à-Pierrot in March 1802. Brintle’s caption reads:

Marie Jeanne Lamartiniere is considered one of the heroines of the Haitian revolution. Little is known of her except that she fought valiantly during the battle of the Crete-a-Pierrot next to her husband, Brigade Commander Louis Daure Lamartiniere. She could be seen over the fortifications, carbine in hand, saber at her side, distributing ammunitions, lighting canons, and constantly encouraging the soldiers to keep fighting. The fort was besieged by the French and all seemed lost when word came from Dessalines that the fort was to be evacuated immediately. That same night, on March 24th, 1802, most escaped when the besieged rebels fought their way through more than 10,000 French troops. This withdrawal was a remarkable feat and won Lamartiniere a name among the heroes of Haiti’s independence. We do not know for sure what became of Marie Jeanne after the retreat from the Crete-a-Pierrot, but it is her bravery, fearlessness and intrepid boldness that make her unforgettable.

This painting - the first in the series of revolutionary women to be created by Brintle - depicts Dédée Bazile, so-called ‘Défilée la folle’. According to the historical narrative, Bazile served as a sutler and led a battalion in Dessalines’ revolutionary army. It is thought that her nickname derives in part from her battle-charge ‘Defilez, defilez!’ (March, march!) After Dessalines was ambushed and assassinated at Pont-Rouge in 1806, Bazile is purported to have recovered his dismembered body parts and carried them to his final resting place. This image evocatively tells that story of grief and re-assembly. Brintle’s caption reads as follows:

We do not know why Defilee was given the surname of La Folle (the madwoman); in fact, not very much is known of Defilee, yet her actions are the epitome of the Corporal Works of Mercy. She was born near Le Cap of slave parents and worked as a peddler. It was said that she so greatly admired Jean Jacques Dessalines that she followed his troops wherever they went. It is this constant admiration that would put Defilee in the proximity of Dessalines when on October 17, 1806 he was ambushed (supposedly by Petion and Christophe) and assassinated at the Pont Rouge, just north of Port-au-Prince. His mutilated body was thrown about. Diligently and without a word, Defilee gathered the remains of her hero in a burlap sack and placed him on one of the tombs inside the cemetery in Port-au-Prince. President Petion subsequently sent two corporals to clandestinely bury Dessalines without official ceremony. Later, a tomb was erected on the remains by Mrs. Iginac which carries the inscription: “Here Lies Dessalines - Dead at 48.”

From Patricia Brintle’s artistic book project exploring the Thirteen Years of the Haitian Revolution, this image celebrates the struggles of the numerous and nameless women who participated in the revolutionary cause through acts of diversion, subterfuge and sagacity. Such women were essential vectors, facilitating the gains made by Haiti’s gwò nègs on the revolutionary battlefield. Brintle notes of such women that ‘The part [they] played in the revolution was vital, yet not as noted as that of men because their roles were not so much on the battleground as in the background of the battles. They were the support group without whom the revolution would not have been successful. They were the ones to bind the wounds and feed the troops; they were the spies, the couriers, the cooks, and the nurses; they were the business managers, the store keepers, the hôtelières and the entertainers; and they were the ones raising the children who would grow up to be the future of this proud nation.’ Brintle’s caption for this artwork reads as follows:

This proud woman sits elegantly with her legs crossed. She wears the colors of the Haitian flag. On her lap she carries a basket of fruit and some bread. On her side is a table with a bowl and some dishes. She waits patiently for a tired and hungry soldier from the French army to trade ammunitions - see the guns under her basket and pistols under her belt and foot. The Haitian revolution is in full swing but the French soldiers are ill equipped to fight under the hot sun. Many, like General Leclerc, succumb to yellow fever; they are hot, hungry and discouraged. These brave women from the plantations trade food for ammunition with the French soldiers and give those to the indigenous army thereby doing their part to win the war. Victory came on December 4, 1803 when Jean Jacques Dessalines won over French forces under the command of General Rochambeau during the battle of Vertieres, near Cap Francais in the north of Haiti.

Another artwork from Brintle’s Thirteen Years series, this image depicts Marie-Claire Heureuse Félicité Bonheur, who, as the wife of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, became the first ‘first woman’ (and later, Empress) of Haiti. Renowned anecdotally as a woman of kindness and compassion, as a nurse and caregiver invested in the idea of educational uplift, she is remembered in the memoirs of the French physician and natural historian Michel Étienne Descourtilz for interceding in his execution ordered by Dessalines. She is represented here in a domestic setting, with a tall, white head wrap tied neatly around her head. Together with her white shawl and cross pendant, her clothing and adornments converge to convey an image of modesty, virtue and devotion. That she wears the colours associated with the Haitian bicolore (curiously not the red and black of the Dessalinian imperial flag but the red and blue of the flag avowedly sewn together by Catherine Flon at the Congress of Arcahaie that became symbolic of the indigènes’ claim to independent statehood) is indicative of her symbolic importance as a woman who helped to shape a sovereign Haiti, free from colonial rule. Dessalines is only figured synecdochically - in the representation of his military uniform, sabre and boots, arranged neatly by the door, and of his bicorne, which Marie-Claire rests upon her lap. By gesturing to Dessalines’s presence ‘beyond the frame’ of this artwork and centring Marie-Claire, Brintle significantly shifts the focus of conventional revolutionary narratives that privilege the accomplishments of military men and gesture only fleetingly to the contributions of their companions. Brintle’s caption reads:

Here we see the wife of Dessalines, Marie-Claire Heureuse Felicite, at dawn waiting for her husband to dress. His uniform is ready, boots are clean and shiny, and she holds his bicorn on her lap. She is a very pious woman and is known for interceding with Dessalines to allow her to feed hungry Haitians during the siege of Jacmel. Following the victory at Vertieres, French General Rochambeau was given ten days to leave with his troops. It was agreed that Dessalines would send the wounded and prisoners back to France. But she knows the fierceness of her husband and wants to plead for the life of the prisoners and ask they be allowed, as promised, to France. History tells us that Dessalines did not listen to her pleas. Instead, he ordered the death of all French and French Creoles from January to April 1804 which resulted in the massacre of close to 5,000 people.

This image from Patricia Brintle’s series of paintings for Thirteen Years depicts Victoria ‘Toya’ Montou alongside Jean-Jacques Dessalines. Said to have been Dessalines’s aunt, the little we know of Toya’s contribution to the revolutionary cause comes to us from a few lines in the memoir of a physician named Jean-Baptiste Mirambeau. According to Mirambeau’s narrative, Montou commanded a small regiment of rebel soldiers during the revolutionary conflict. Dessalines, who attended Montou on her deathbed in 1805, is claimed to have said to her nurse, ‘This woman is my aunt, take care of her as you would have taken care of me myself, she had to undergo like me all the sorrows, all the emotions during the time that we were condemned side by side to work in the fields.’ Depicted here in sumptuous garments of red and gold, Montou’s appearance is almost regal, greatly overshadowing the figure of Dessalines, who is envisioned in the plain and commonplace garments that he would have worn as an enslaved field labourer prior to the revolution. In this way, we see that the histories of Haiti’s great military men extend beyond the military moment, and comprise, above all, the stories of others - of families both real and forged in adversity, of communities, elders and mentors, and of the women so vital to those networks. Brintle’s caption reads:

The scene finds a young Jean Jacques Dessalines in deep conversation with his aunt Gran Toya. Victoria Montou, also known as Adbaraya Toya was a female soldier and freedom fighter in the army of Jean Jacques Dessalines. Before the revolution Toya worked alongside Dessalines as a slave. Intelligent and energetic she fought as a soldier in active service and even commanded soldiers during battle. She had great influence on many who fought in the revolution. She was from Dahomey, now Benin, where she served as a member of the council of women in the kingdom known as the Dahomey Amazons who fought to protect the kingdom. She was a healer and worked on the Cormier plantation where she became close to Marie Elisabeth, the mother of Dessalines who entrusted her son to her before she died. Toya was Dessalines counsellor in all affairs and when she died, she was given a state funeral.

This interpretation of Catherine Flon by Patricia Brintle shows her wearing an ornately embellished, sleeveless yellow dress—a perhaps more modern style than the one worn by the Catherine Flon of Brintle’s earlier series of revolutionary women. Her head wrap, or madra, is piled high upon her head and tied in a bow. Its decorative function is enhanced by accessories which include gold earrings and a gold necklace and bracelet. Like the women of colonial Saint-Domingue who demonstrated creativity and defiance in the face of sumptuary laws, Brintle’s Catherine Flon channels a similar defiance and ingenuity as she stitches together the Haitian bicolore. Though this symbolic act is believed to have taken place at the Congress of Arcahaie, which saw the unification of revolutionary forces under the military leadership of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Brintle makes Catherine Flon the protagonist of this saga by showing her in isolation, removed from the scene of military diplomacy. By placing her in the natural surroundings of Ayiti’s mountains, she is also rendered a temporally indeterminate figure, which is compounded by the indeterminate periodicity of her clothing. Catherine Flon is thus seen as both a woman of the past—whose creativity stretches back into the colonial imaginary—and also a woman of now—whose skills remain integral to the fabric of Haitian society.

This painting depicts Cecile Fatiman, a manbo who, along with Boukman, is said to have presided over the Vodou ceremony at the elusive Bwa Kayiman that cemented the plans for rebellion among the enslaved rebels that took part in the uprisings across the Plaine du Nord in August 1791. Her bright red and orange dress gestures symbolically to the flames that would engulf the plantations set ablaze by the insurgents. Though Brintle’s Fatiman appears far removed from the ceremonial festivities of Bwa Kayiman—a solitary figure flanked by verdant mountains—she carries the paraphernalia that root her in the historical moment: the head of a creole pig—who was sacrificed and whose blood was drunk during the Vodou ceremony—and a drinking vessel displaying the veve, or symbol, of Ogoun—the Vodou lwa associated with fire, often credited with fomenting rebellion in the minds of the enslaved. Like Brintle’s 2021 depiction of Catherine Flon, her representation of Cecile Fatiman is both timeless and modern. Though Fatiman’s existence and the veracity of the ceremony over which she presided have been disputed by some scholars, she thus cements herself as an icon whose symbolic importance in the Haitian popular imagination transcends the limits of conventional historical narratives governed by white colonialist epistemologies.

Like Patricia Brintle’s 2012 representation of Marie-Jeanne Lamartiniere, her 2021 interpretation of Marie-Jeanne shows her at the very heart of the scene of military encounter, waving a battle flag and carrying the accoutrements of battle, which include her sword and rifle. Unlike Brintle’s earlier depiction, however, this Marie-Jeanne stands defiantly astride a cannon on top of the ramparts and her banner bears the Kreyòl slogan ‘ABA ESKLAVAJ’: ‘Abolish slavery’. The iconography of Brintle’s painting echoes various historical representations of Marie-Jeanne, including those of Bellegarde, Madiou and Dorsainvil, who all depict her as a sabre-wearing, rifle-brandishing warrior who showed herself to be vital at the decisive battle of Crête-à-Pierrot in the Haitian campaign for independence. Curiously, neither of Brintle’s representations of Marie-Jeanne depict her in the mameluke/mamluk style costume with sirwal/saroual (harem) pants that she is described to have worn by Bellegarde. Instead, she wears a long skirt whose flowing fabric billows in the wind like a flag - an analogy that is compounded by the predominance of red and blue, which evokes the colours of the bicolore. The banner that she brandishes and the political message that it communicates roots her within a historical tradition of protest and activism whose branches extend into the present. That this painting was produced in 2021 in the wake of the murder of George Floyd and the global rise of the Black Lives Matter movements and the popular movement against corruption and impunity in Haiti following the Petrocaribe scandal lends weight to this notion. Like the other women in her more recent series of revolutionary women, Brintle’s Marie-Jeanne is shown to be a woman of the past and the present: a woman worthy of historical recognition and restitution, and a source of sustenance and resilience for the fight ahead.

Though rooted Black vernacular aesthetics, Brintle’s depiction of Sanité Belair references the neoclassical and resonates strikingly with Anne-Louis Girodet’s 1797 portrait of Haitian revolutionary Jean-Baptiste Belley. Like the Belley of Girodet’s painting, Sanité leans against a column—a common motif of neoclassical paintings. Unlike in Girodet’s painting, however, Brintle’s Sanité is not placed in conversation with a tradition of white bourgeois intellectualism. Whereas Girodet’s painting—which shows the Abbé Raynal mounted on top of the plinth on which Belley leans—can therefore be seen as a meditation on the abolition of slavery as a project of the Enlightenment, Brintle’s painting pays exclusive tribute to Haitian militarism, creativity and defiance. In this way, Haiti is thrust into the foreground as a protagonist in the universal campaign for abolition as the first nation to universally and permanently abolish slavery. Moreover, by transposing the figure of Sanité onto that of Belley, Brintle reinforces the importance of women’s stories of insurgency. Though she is depicted in full military regalia, complete with epaulettes and bicorn hat as in Richard Barbot’s representations, her androgynous appearance is undercut with allusions to her femininity, such as her gold earrings, her madra and the calla lily which she holds in her right hand. A flower native to the southern African continent, the calla lily also references the circuitous and historic routes taken by Haitian women and women in the Haitian dyaspora. However, the abundance of vegetation, especially the sprawling shrub which reaches up from the ground and brushes against Sanité’s hand, reinforces her rootedness in the Haitian popular imagination. Executed on the orders of Dessalines, Sanité did not get to write her own story; Brintle and others have rehabilitated her in the present.

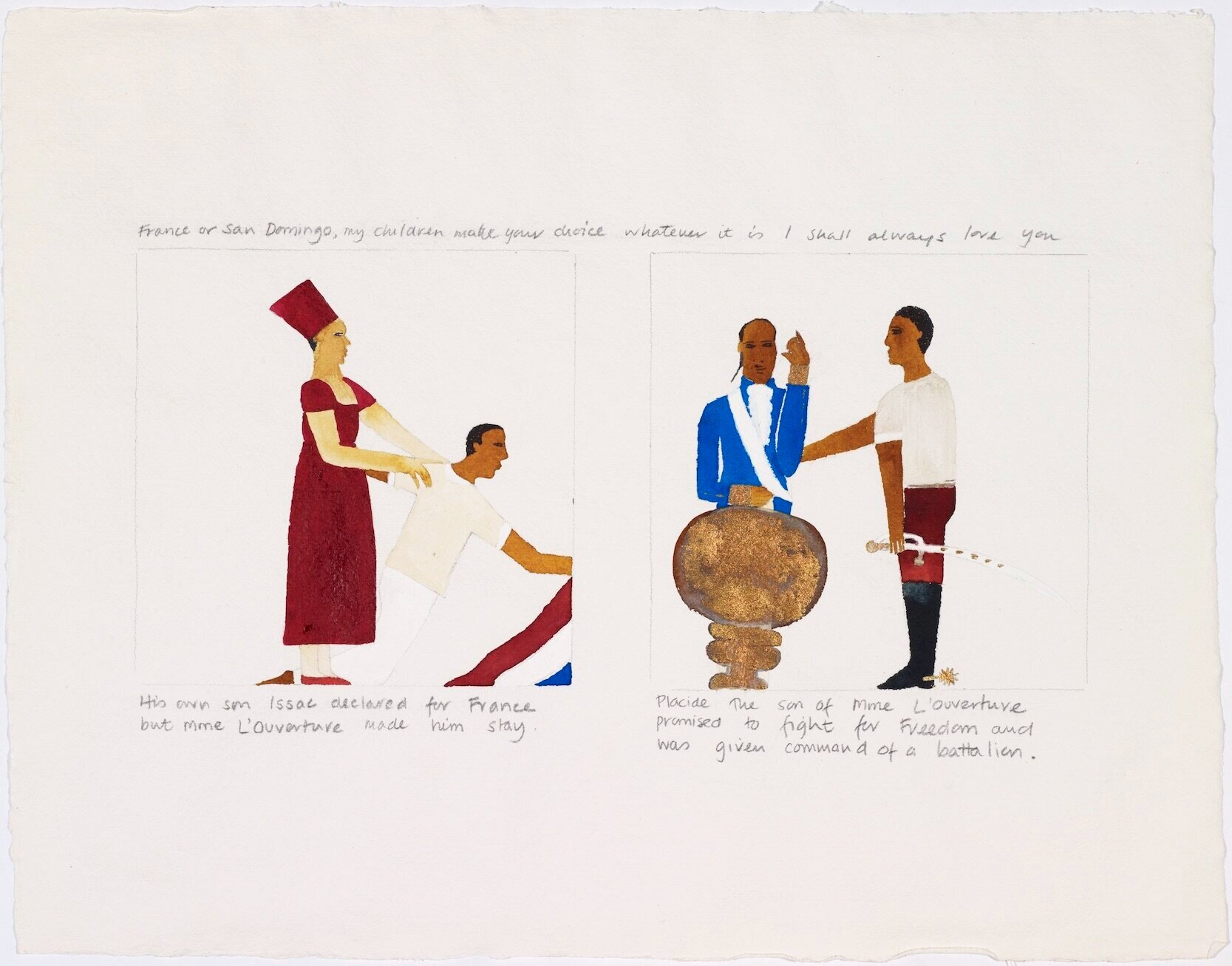

Scenes from the Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture is a series of watercolour paintings on paper created by Turner Prize-winning artist Lubaina Himid OBE in 1987. It consists of 15 works in total, each exhibiting a diptych of two images in conversation with each other. Inspired heavily by C. L. R. James’s seminal text The Black Jacobins, the series celebrates the heroism of revolutionary general Toussaint Louverture. However, it also thrusts into the foreground the unexplored, under-acknowledged and undocumented histories of revolutionary women and the myriad ways that they contributed to the revolutionary saga. In her co-authored book Inside the Invisible: Memorialising Slavery and Freedom in the Life and Works of Lubaina Himid, Himid observes of the series ‘I wanted children to know about this extraordinary episode in the politics of the black diaspora and painted in a way that I hoped would appeal to publishers. In a way, the work resembled a graphic novel with minimal text and was to be read in a linear way. The paintings were done in soft and gently colourful watercolour, sending out friendly and accessible information about ordinary days in the life of an exceptional man.’

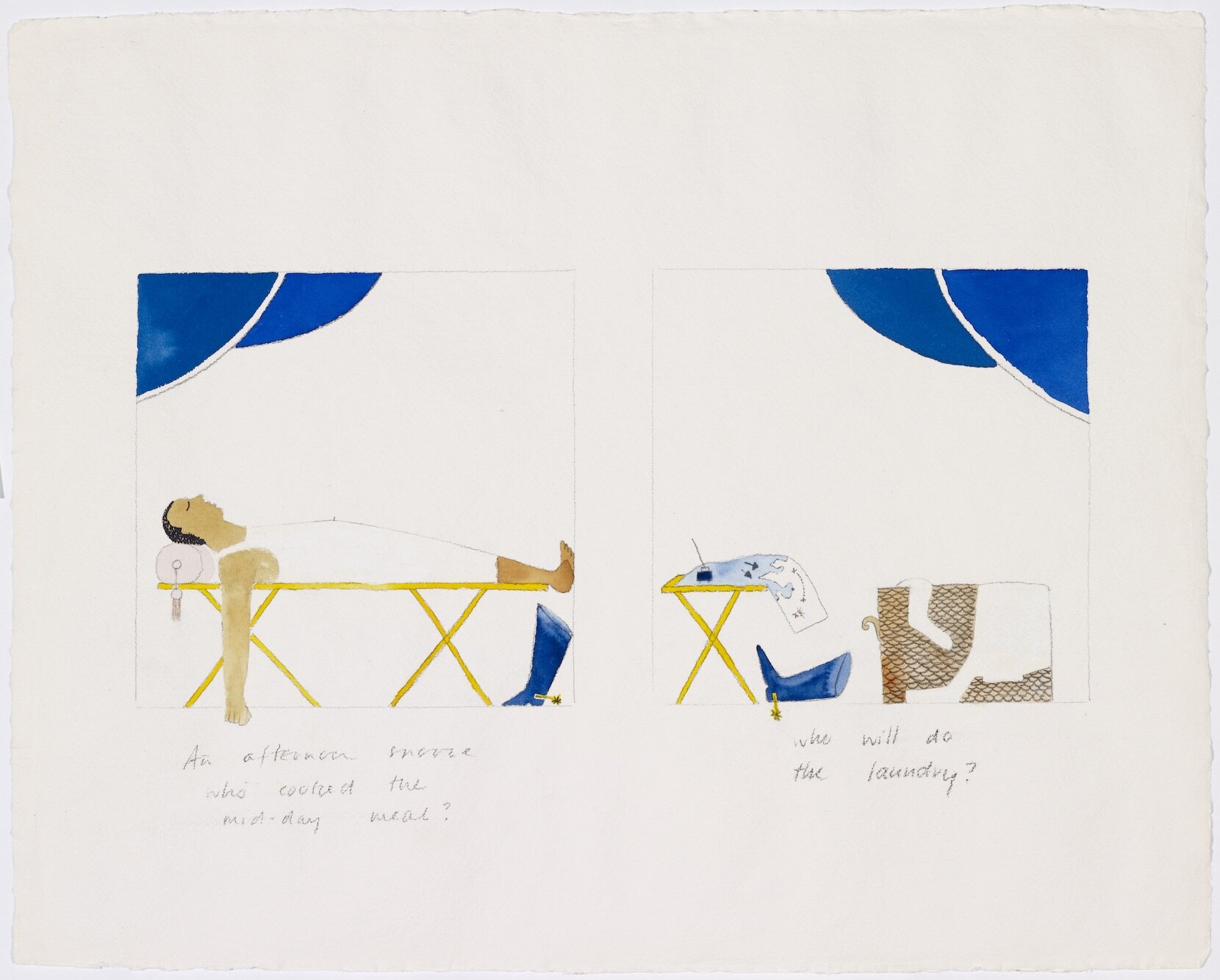

In this diptych, the second image in the series, Louverture is shown in repose, reclining on a cot, his discarded clothes and the paraphernalia of war strategy strewn about the space that he inhabits. The captions on the images read ‘An afternoon snooze / who cooked the midday meal?’ and ‘who will do the laundry?’ In asking these questions, Himid not only signifies the absented and undocumented female figure that grand historical narratives so often occlude in their emphasis on military heroism but also gestures to the importance of domestic and emotional labour undertaken largely by women both at home and on the battlefront.

In this diptych, the fourth in Lubaina Himid’s Scenes from the Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture series, Himid engages with the themes of fugitivity and marronage.

The first image shows a woman in joyous, rhythmic motion, as if in flight, limbs stretching beyond the parameters of the frame, presumably dancing to the sounds of the bamboula drum generated by the synecdochic hand that reaches into the image from beyond the frame. The caption reads ‘The people danced, there was drumming’.

The second image in the diptych shows the mountainous terrain that concealed many maroon communities in Saint-Domingue prior to the revolution. Signs of community and rebellious strategies of communication are gestured in the fires that spring up from the hillsides. The caption reads: ‘There were signs across the country from plantation to plantation’.

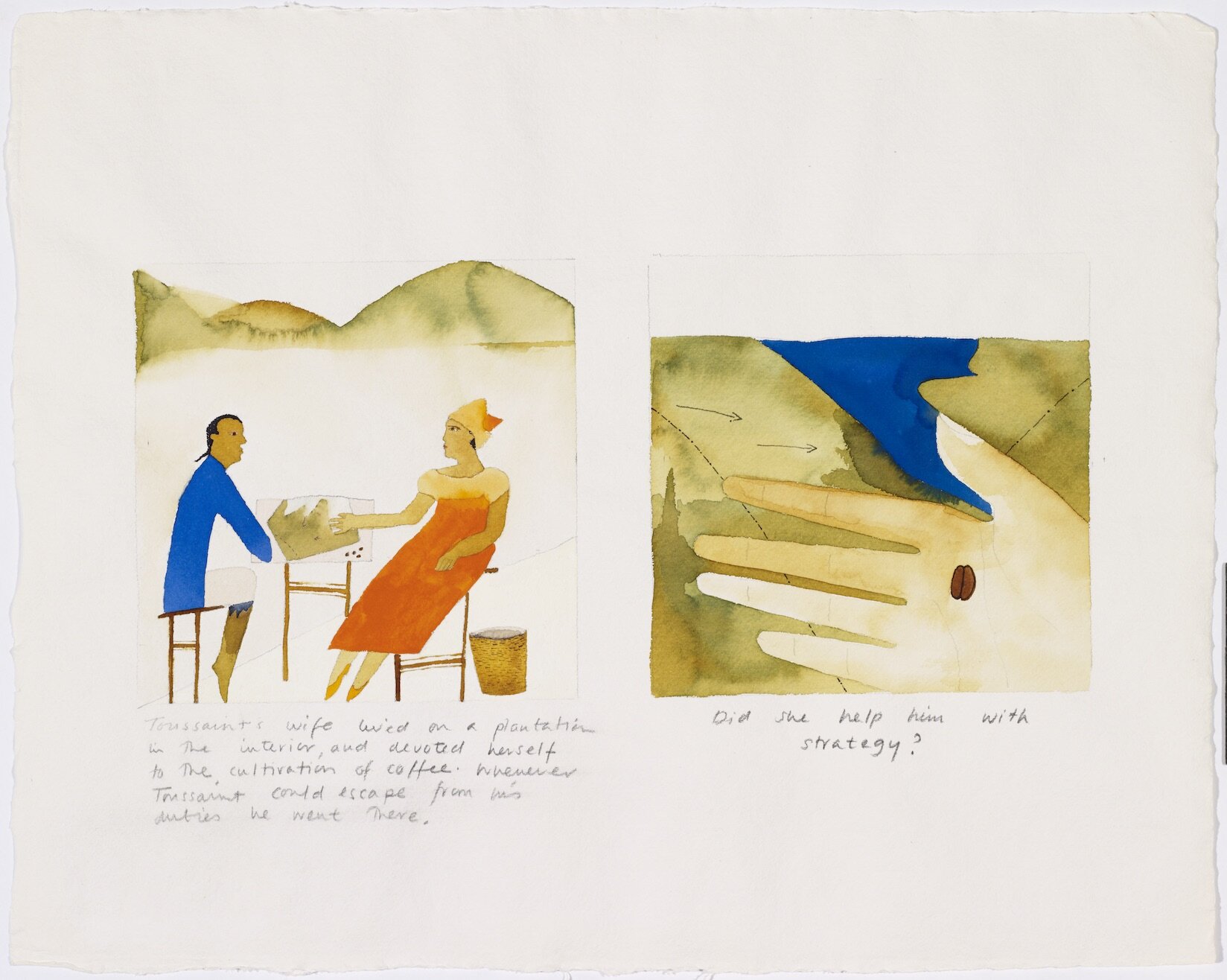

The fifth diptych in Himid’s Scenes from the Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture series depicts Toussaint in the domestic setting of his home plantation with his wife Suzanne.

In the first image of the pairing, Suzanne is shown wearing an orange dress and head wrap seated at a table opposite Toussaint. A map has been spread across the table and several coffee beans, which presumably serve as figurative pawns, are clustered at the edge of the map. The caption reads: ‘Toussaint’s wife lived on a plantation in the interior, and devoted herself to the cultivation of coffee. Whenever Toussaint could escape from his duties he went there.’

The second images focuses in on a single open hand holding a coffee bean, gesturing to the possibility of collaboration and the many ‘hands’ that contributed to revolutionary strategy, but speaking specifically, here, to the strategic contributions of Suzanne. The caption asks: ‘Did she help him with strategy?’

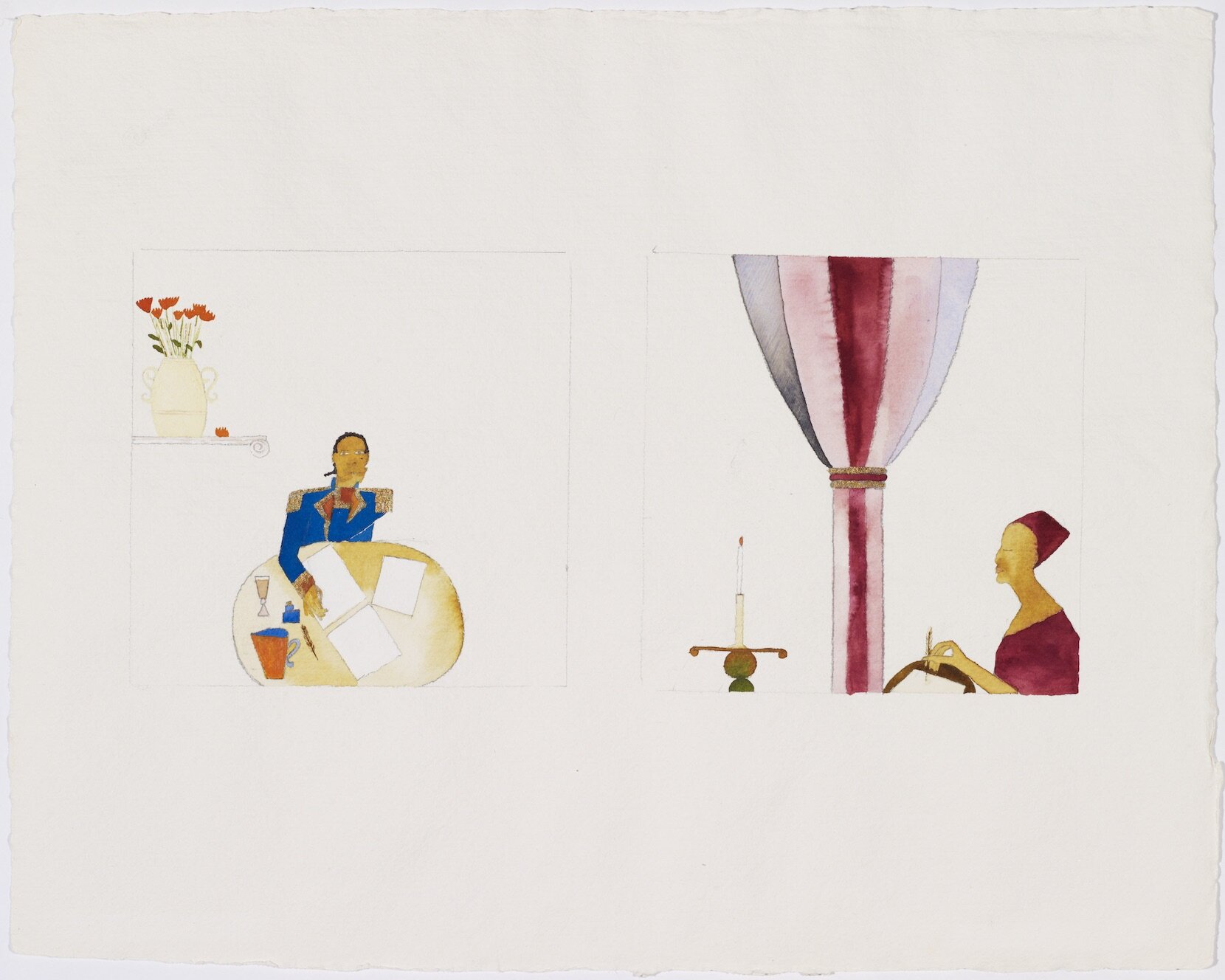

The images in the seventh diptych from Himid’s Scenes from the Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture form a mirror to one another. We see, on one side, Toussaint seated at a desk in full military regalia, presumably writing a letter to Suzanne, who is shown in the second image writing back. The lone candlestick serves to highlight the solitude of her environment and signals her foremost importance within the household in Toussaint’s absence.

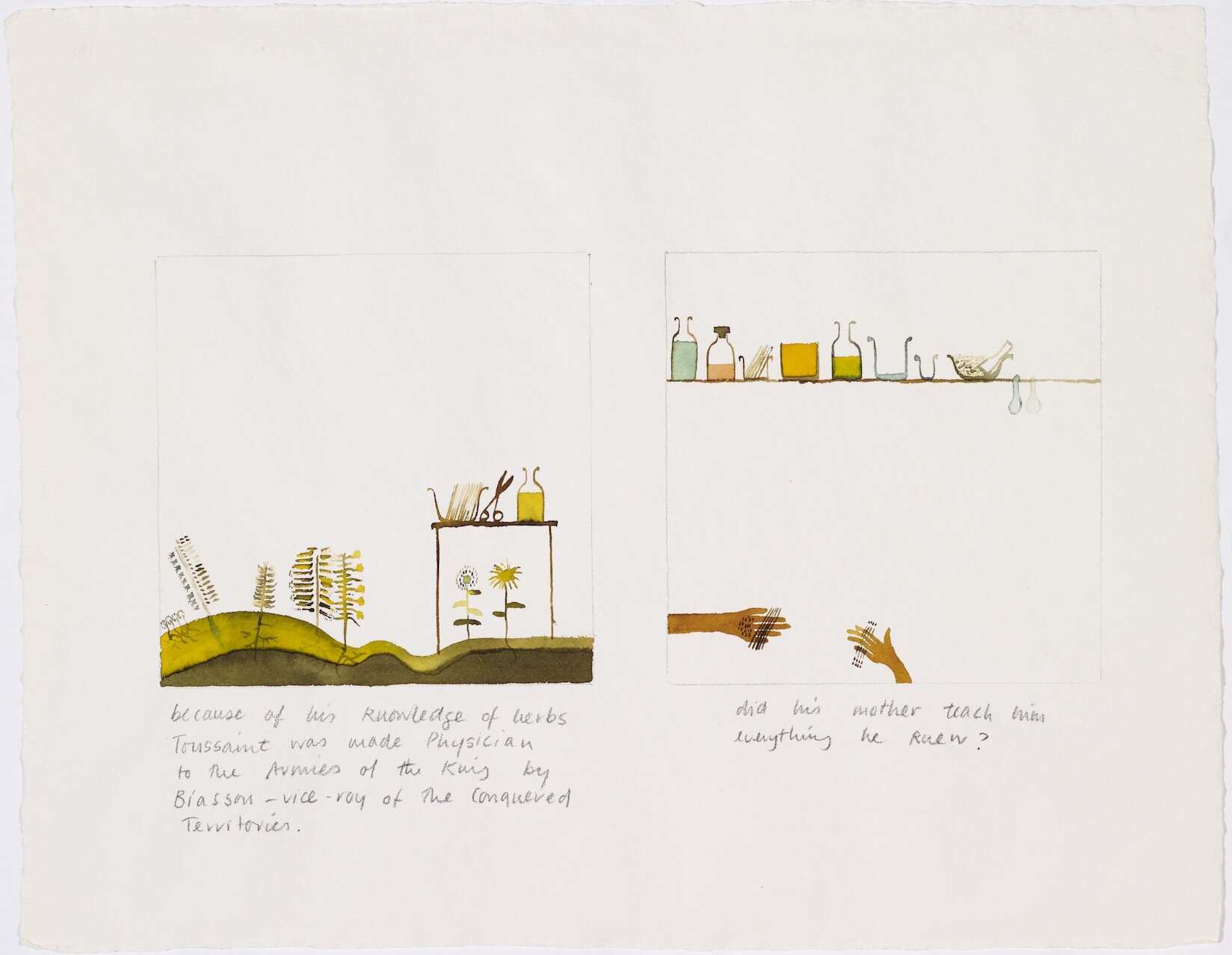

In this diptych, the seventh in the series of Himid’s Scenes from the Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture we are introduced, once again by way of a synecdochic hand, to another occluded female figure in the saga of Toussaint’s life: that of his mother.

The caption to the first image in the diptych, which shows a variety of flora and a collection of grooming implements and vials reads: ‘because of his knowledge of herbs Toussaint was made Physician to the Armies of the King by Biassou - vice-roy of the Conquered Territories.’

The second image shows two hands juxtaposed with one another: one larger and, we are led to infer, representing Toussaint’s absented mother and the other representing the childlike hand of Toussaint. Each hand is shown cupping the natural components that, we are led to assume, form the basis of one of the healing concoctions that line shelf that floats above the scene. The caption reads ‘did his mother teach him everything he knew?’

This diptych, the fifteenth in Himid’s Scenes of the Life series, explores the challenges confronting military wives and mothers and the general strain of military life on domestic normality as we are introduced, for the first time, to Louverture’s adult sons Isaac and Placide.

The caption to the first image reads: ‘His own son Isaac declared for France / but L’Ouverture made him stay’. The caption to the second image reads: ‘Placide the son of Mme. L’Ouverture promised to fight for Freedom and was given command of a battalion.’ The diptych is unique, however, in that, in addition to the individual image captions, a single overarching caption unites the two images amplifying a nondescript voice of parental authority. It reads: ‘France or San Domingo, my children make your choice / whatever it is I shall always love you’. Though the mention of ‘his own son’ in the caption to the first image might lead us to assume that this ‘voice’ represents the voice of Toussaint, the presence of Suzanne in this same image unsettles any simplistic correlation.

Born in Port-au-Prince in 1961, Richard Barbot now lives in Montreal. An artist and illustrator, he was commissioned in 2004 by the Banque de la République d’Haïti to produce a bust of Sanité Bélair for the 10 gourdes banknote issued in commemoration of the bicentenary of Haiti’s independence (reproduced below). Sanité remains a figure of interest for Barbot, as reflected in this more recent work, which shows her in full military regalia, complete with epaulettes and a bicorn hat. Barbot describes Sanité as ‘one of the most symbolic heroines of Haiti’s independence. In the face of betrayal and death she demonstrated unmatched bravery and strength.’ Her furrowed brows encode a story of strain and strife, reminding us that, like many other women who contributed to the revolutionary saga, she made epic sacrifices. Speaking of his motivation behind the painting, Barbot observed ‘History tends to erase the traces of women who have played an important role in the past. I find it important to represent them so that their memory will last.’

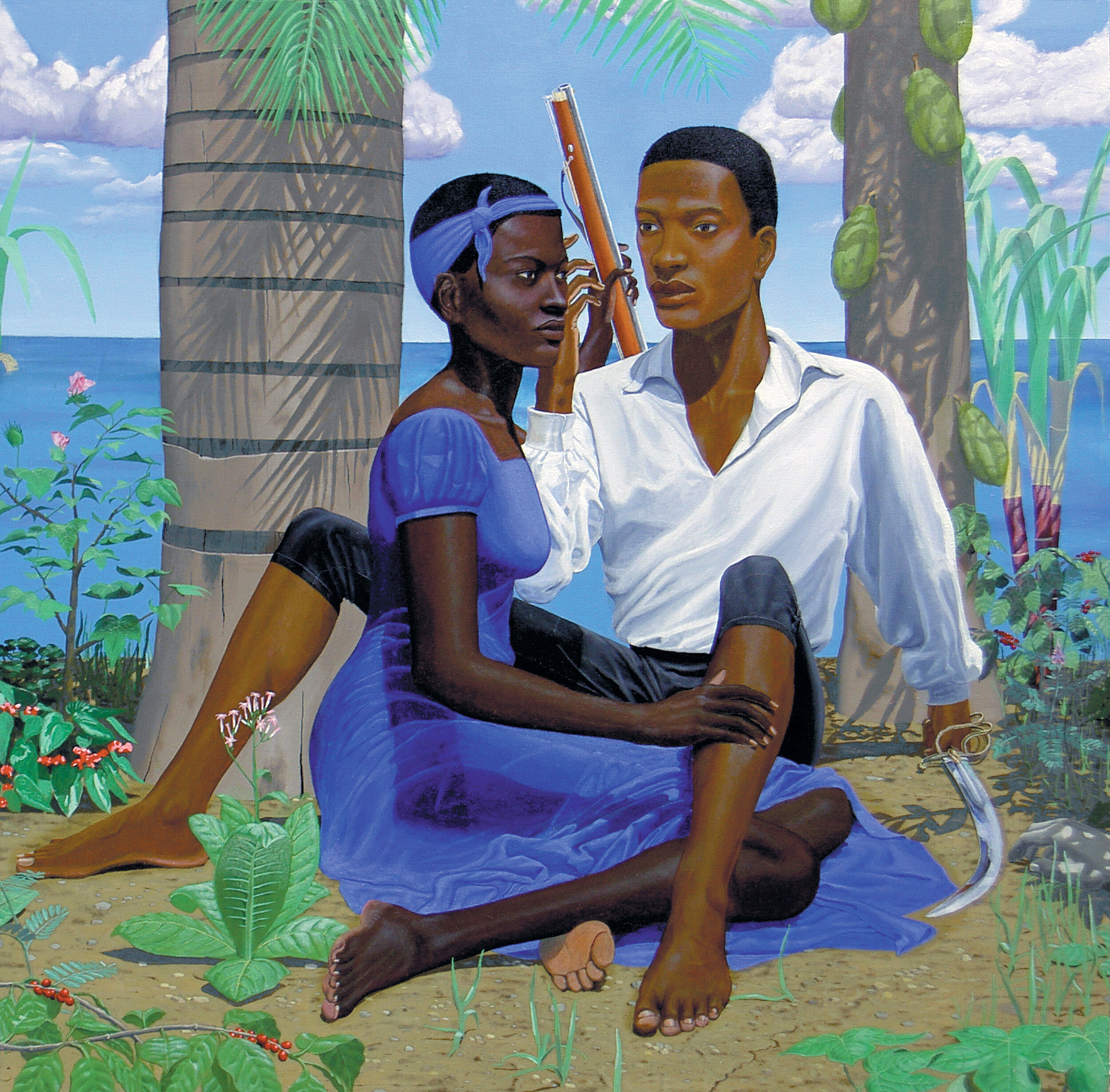

Based in London, Kimathi Donkor is a contemporary artist of Ghanaian, Jamaican and Anglo-Jewish heritage. Many of his artworks recreate historical scenes of Black Atlantic heroism, often striving to amplify stories elsewhere invisibilised and occluded in white, colonialist histories. Several of his works focus on figures from the Haitian revolutionary saga. This image features as its protagonists Charles and Sanité Belair, who are shown nestled in a clifftop clearing between island and sea, surrounded by wild tobacco, cotton, sugar and indigo - the lucrative crops of colonial slavery. Capturing a rare moment of tranquility and solitude, it presents a vision of Sanité that contradicts the character envisioned by historical chroniclers such as Madiou, who describes her as a ‘brigande’ and imagines her as the protagonist of violent atrocities avowedly committed by the renegade indigènes with whom she was associated. While she is so often depicted in artistic renderings in military regalia, she is here depicted wearing a delicate blue empire-line gown with a kerchief or madra in a matching hue tied around her head, emphasising her femininity. She is shown in the loving embrace of her husband, their limbs interlocking and their hands interlaced around a musket as if in anticipation of impending assault. By envisioning her thus, Donkor humanises and renders fallible the woman immortalised in public history as a ‘tigress’.

Dame Cheruxi was a lady-in-waiting in the company of Marie-Louise Christophe during the era of the Haitian Kingdom (1811-1820). She was also Marie-Louise’s purported goddaughter. Accorded the court name ‘Coeur enflammé’, Dame Cheruxi was born in 1803 to a woman of colour named Marie-Augustine Langlois and a Frenchman by the name of Richeux de la Roche Asnière (Cheruxi is an anagram of Richeux) who left Saint-Domingue for a brief period around this time owing to the revolutionary unrest. At the time of her birth, interracial marital unions were still legally forbidden, but Richeux left a notarised document acknowledging his paternity. He returned to Haiti in 1806 but died shortly afterwards from Tetanus.

The descendants of Dame Cheruxi have preserved a number of items from her personal collection, including (in addition to this portrait), hair clips, jewellery, and a dress donated in 2015 to the Musée du Panthéon National Haïtien (MUPANAH). She is depicted here in a rare nineteenth-century portrait by an unknown artist wearing a chemise gown with gathered sleeves, tapered waist and exposed décolletage similar to the chemise gown now in MUPANAH’s collection. It is edged with lace fringe and she is shown to be wearing a string of pearls and gold earrings.

Objects

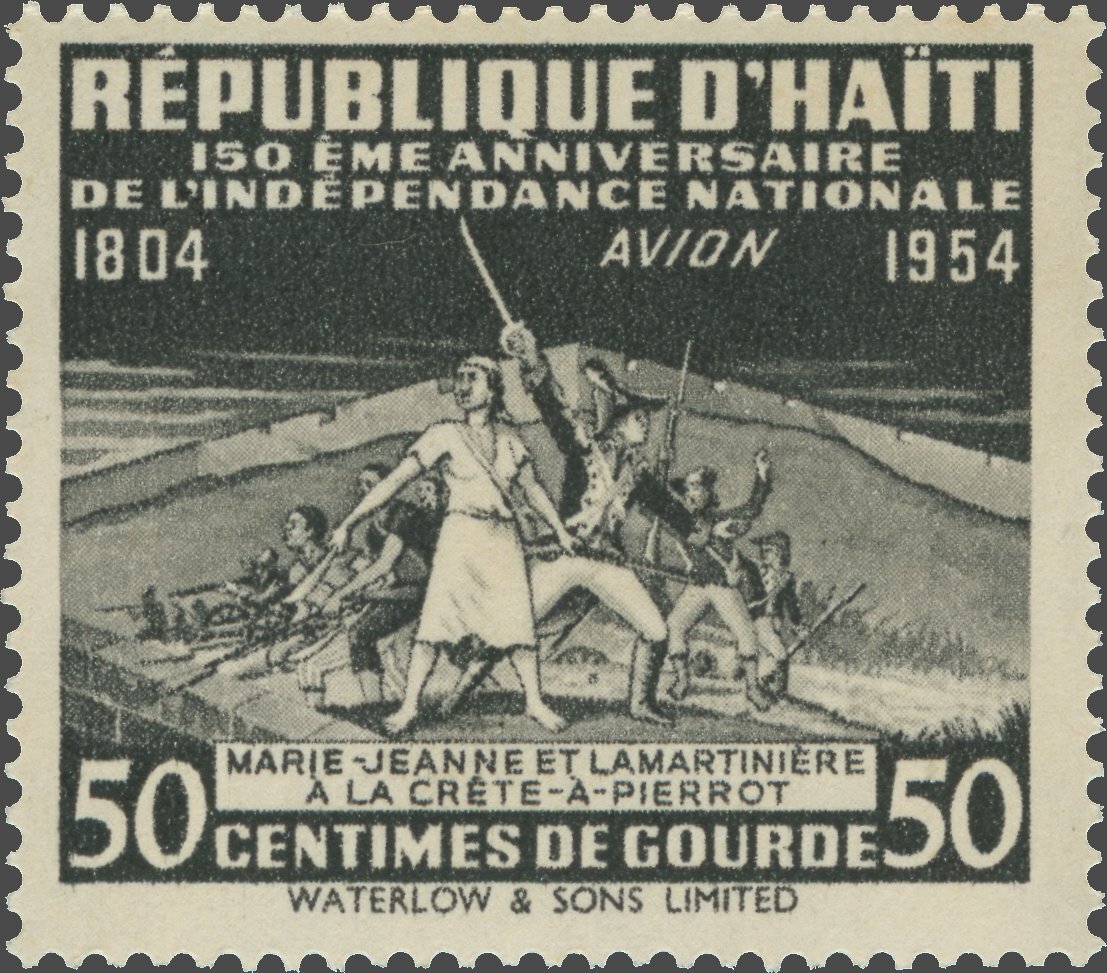

This stamp, produced as part of a series for the 150th anniversary of Haiti’s independence in 1954, depicts a scene from the siege of Crête-à-Pierrot, a decisive battle in the Haitian Revolution. The illustration used for the series commemorates the heroic deeds of Marie-Jeanne, a female soldier said to have been the wife of Louis Daure Lamartinière, who is shown flanking her on the right. While Marie-Jeanne represents an enigmatic figure whose story has been highly mythologised by the chroniclers of Haitian history, the circulation of her image via stamps and coinage at significant moments of national remembrance has nevertheless served to rehabilitate within the national imaginary acts of female heroism that have been largely undocumented, marginalised and neglected. In this illustration, Marie-Jeanne is shown wearing a long tunic with a kerchief or madra on her head. Her arms are raised at her side as if to form a protective shield against the insurgent French army. In her right hand she holds a sword and a rifle is slung over her back. This representation echoes imagery that we find in Bellegarde, where she is described in these exact terms.

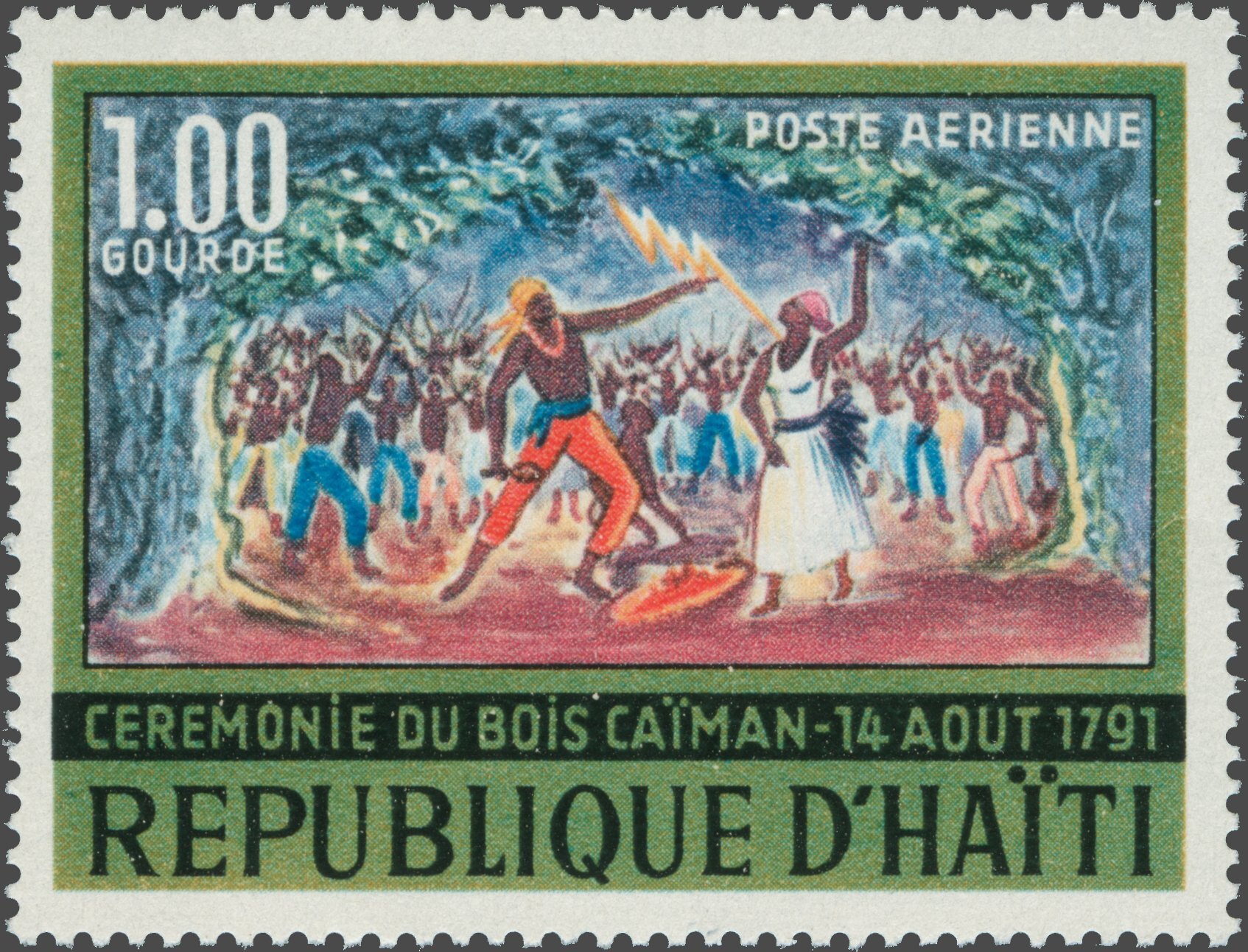

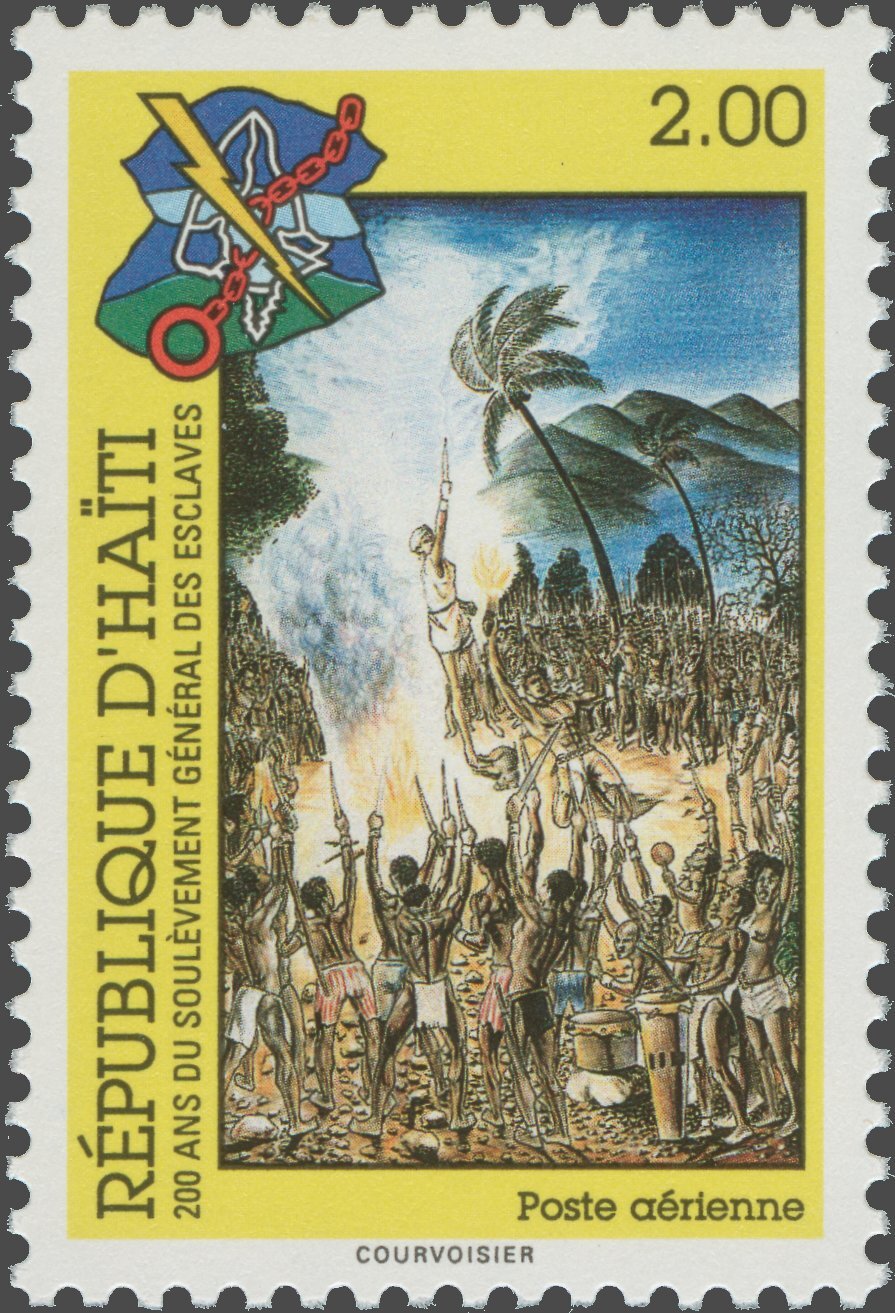

This stamp, issued in 1968, features artwork produced by the Haitian painter Raoul Dupoux (1906-1988) depicting the Vodou ceremony at Alligator Wood (Bois Caïman or Bwa Kayiman) led by the houngan Boukman and the manbo Cécile Fatiman in August 1791. The event is believed to have triggered the slave rebellion that broke out on August 23 and led to a series of insurgencies across the northern territory of Saint-Domingue thereafter. Much like the ceremony itself, the story of Cécile Fatiman is highly contentious, some anecdotal accounts suggesting that she may have been a sister of Marie-Louise Christophe (conflating her history, it would seem, with that of Généviève Coidavid Pierrot). In this image by Dupoux, Fatiman is depicted in a white dress (white has a special ceremonial significance in Vodou) and a red head kerchief or madra.

This stamp, issued in 1991 in commemoration of the bicentenary of the slave insurgency that marked the beginning of the Haitian Revolution, features another image of the Bois Caïman/Bwa Kayiman ceremony. The image chimes with many popular accounts which hold that the ceremony was marked by the sacrifice of a kreyòl pig. Cécile Fatiman is shown at the centre of the image, standing next to a kneeling Boukman in a white tunic and bandana or madra, with the sacrificial pig at her feet.

This 1 Gourde coin from the collection of Joseph Guerdy Lissade was minted in 1820 by the Kingdom of Haiti. It is unique in that the reverse-side of the coin is inscribed not only with the initials of Henry (H), but also of Marie-Louise (ML) Christophe (the M and L interlaced). Marie-Louise was the only woman to have lived through the revolution to be recognised on official Haitian coinage in the period of early sovereignty and remains one of only several identifiable women in Haiti’s history to be recognised on state-issued coinage at all. It bears the familiar motif from Christophe’s coat of arms of a phoenix rising from the flames encircled by the words ‘EX CINERABUS NASCITUR’ (Je renais de mes cendres/I am reborn from my ashes). The central motif and both sets of initials are topped with the emblem of a crown. The outer rim bears the motto ‘DEUS CAUSA ATQUE GLADIUS MEUS’ (‘Dieu, ma cause et mon épée/God, my cause and my sword). The obverse bears the bust of Henry I crowned in a laurel wreath in military uniform overlaid with a classical-style chiton with the motto ‘HENRICUS DEI GRATIA HAITI REX’ (Henry roi d’Haïti par la grâce de Dieu/Henry king of Haiti by the grace of God). See Joseph Guerdy Lissade, Henricus Dei Gracia Haiti Rex: Monnaies et Médailles de l’Etat d’Hayti, 1807-1811 et du Royaume d’Hayti, 1811-1820 (Grissom Company, 2007), pp. 20, 71.

This commemorative 100 gourdes coin, minted in 1970 during the reign of François ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier, is inscribed on the obverse with the name and bust of Marie-Jeanne Lamartinière. As in the 1954 commemorative stamp, Marie Jeanne is depicted wielding a sabre or machete with a bandana or madra on her head, her hair trailing defiantly out of the sides (once again recalling the vision of Bellegarde, who describes her ‘bonnet’ which ‘emprisonnait son opulente chevelure dont les mèches rebelles débordaient de la coiffure’). The reverse bears the Haitian coat of arms and a banner inscribed with the motto ‘L’UNION FAIT LA FORCE’ (Strength in Unity). The outer rim is inscribed with the words ‘LIBERTÉ ÉGALITÉ FRATERNITÉ.

This commemorative 10 gourdes banknote was issued in 2004 to mark the bicentenary of Haitian independance, proclaimed by Jean-Jacques Dessalines on 1 January 1804. It features an artistic reconceptualisation of Suzanne ‘Sanité’ Bélair, produced by Haitian artist Richard Barbot. Sanité, described by Thomas Madiou only as ‘la femme’ of General Charles Bélair, is recounted as having fought at his side during the Haitian revolutionary conflict. Often unforgiving, the chroniclers of Haitian history have emphasised ‘les barbaries’ committed at the hands of Sanité who, along with Bélair, broke from Dessalines and other revolutionary compatriots still then fighting under the banner of the French flag. Along with a handful of other renegades, they led a failed insurgency, subsequent to which Sanité was captured. According to Madiou, Bélair, unable to bear his separation from Sanité, gave himself up to French colonial forces. The prisoners were granted no clemency by their captors and were sentenced to death on 5 October 1802 (Bélair by firing squad, in recognition of his rank as a brigadier general, and Sanité by decapitation). As Madiou recounts, Sanité demanded that she, too, be granted a soldier’s execution. Purportedly refusing a blindfold, she heeded her husband’s entreaty to die bravely.

This dress, donated to MUPANAH in 2015 and formerly in the collection of Maryse Von Lignau, belonged to Dame Cheruxi, once lady-in-waiting in the royal court of Christophe. Painstakingly restored in Paris by textile restorer Ségolène Bonnet, it is described as a white cotton muslin gown. It is held together at the back with metal fastenings and has a bodice reinforced by whalebone. It features a wide hem and fine floral embroidery which forms a garland around the width of the skirt. Such a piece was likely to have been manufactured in Europe - a clear indicator of wealth and status. Though it has many of the features of cotton chemise gowns that were popular in the French Atlantic (both in the metropole and in the colonies) from the late eighteenth century onwards (including the gathered sleeves that were made iconic by Marie-Antoinette) and was initially described as a ‘robe Empire’, the lower waistline is indicative of the fact that the dress is probably from a slightly later period, according to Bonnet (around 1830).

Such material artefacts offer rich, personalised insights into the lives of women so often obscured and occluded in colonialist archives, bearing witness to the creative strategies used by women to make meaning in the age of slavery and beyond.

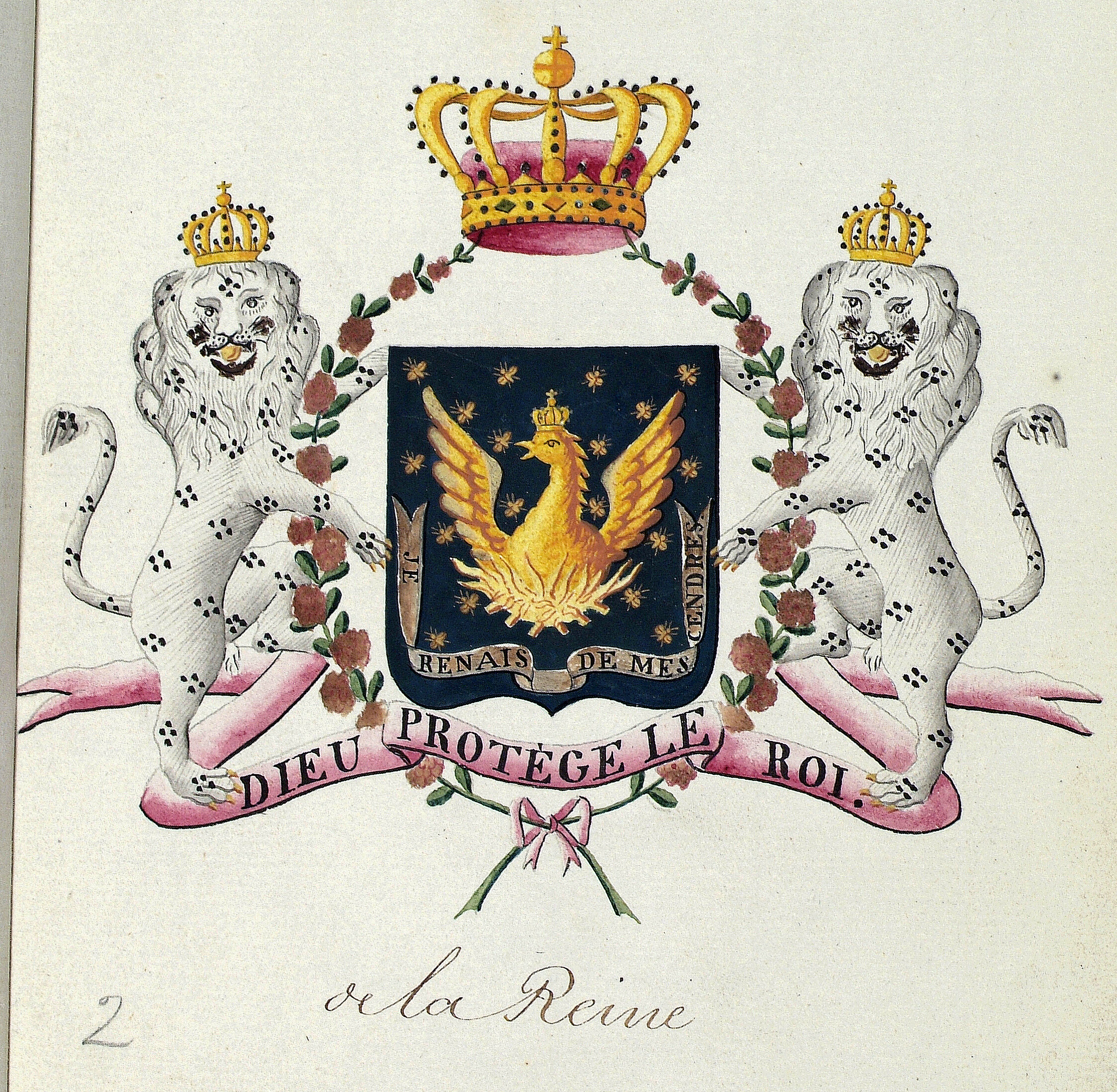

Queen Marie-Louise Christophe (née Coidavid) was the only woman from the court of Henry Christophe to be honoured with her own heraldic arms. As an elite woman of colour, Marie-Louise left more indelible traces than the numerous and nameless women who contributed vitally to Haiti’s revolutionary founding who have nevertheless been occluded from the archives and, subsequently, marginalised in written history. Forged in the fires of anticolonial revolution, Haiti became the first independent Black republic in 1804 and was the first country in the world to permanently, unequivocally and universally abolish slavery. For some, Christophe’s Kingdom of Haiti (established in 1811) represents a betrayal of its revolutionary values and its radical founding. However, within the context of a hostile, white-supremacist, colonialist North Atlantic world, the Kingdom of Haiti represented the very apotheosis of Black radicalism.

The Queen’s arms mirror those of the King’s with a phoenix rising from the flames against a field of blue surrounded by a semy of bees and a banner bearing the motto for the Kingdom, ‘JE RENAIS DE MES CENDRES’ (I am reborn from my ashes). The field is upheld by two crowned lions and encircled by a garland of roses (in place of a chain and pendant of the royal and military Order of St Henry which features in the King’s arms). They are poised on a banner bearing the Queen’s motto ‘DIEU PROTE!GE LE ROI’ (God save the King). A more detailed account of the heraldic symbolism of these and other arms can be found in the College of Arms’s manuscript on The Armorial of Haiti: Symbols of Nobility in the Reign of Henry Christophe.

Sounds

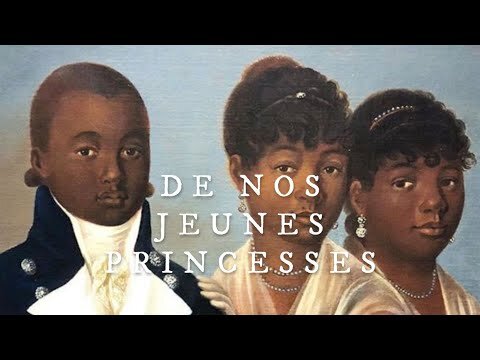

De nos jeunes Princesses

L’esprit, les heureux dons

Répandent leur ivresse

Sur notre nation.

Tout nous dit que les grâces

Ont changé de séjour,

On le voit à leurs traces

Ornements de la Cour.

Reflections from Henry Stoll

“De nos jeunes Princesses” is the sixth song in L’Éntrée du Roi, en sa capitale (1818), a one-act opéra comique by Juste Chanlatte, secretary under Henry Christophe. In the opera, La Limonadière, played by Sophie Araud, discovers, while searching her pockets, that she has lost the song she intended to sing. Damis, played by Chanlatte himself, seizes upon this opportunity to hand her “De nos jeunes Princesses,” exclaiming “I would be well pleased if the merits of this work could equal the zeal with which I had composed it.” Finding herself familiar with the tune—“Ah! Ah! It’s to the tune: Généreuse Lisette”— La Limonadière proceeds to sing the praises of the young princesses, Améthyste and Athénaïre.

Easy to sing, and with a wistful lilt, the melody comes from “Ô ma tendre Musette,” a romance with music by Pierre-Alexandre Mosigny and words by Jean-François de La Harpe. In L’Éntrée du Roi, en sa capitale, it is rather identified as “Généreuse Lisette,” referring to a parody by Louis Jules Mancini Mazarini, the Duke of Nevers.

Dans le cœur de Marie

Les aimables vertus

Ont fixé leur patrie,

Leurs nobles attributs.

Idoles de ces beaux climats

Les bienfaits naissent sur ses pas;

Par sa présence

La bienfaisance

Sait acquérir un nouveau prix:

Célébrer cet objet chéri,

N’est-ce pas célébrer Henry? (bis.)

Auguste et tendre mère

De son sexe ornement,

Du trône ange prospère

D’Henry soutien charmant ;

Elle ajoute à ses verts lauriers

L’éclat des tendres oliviers ;

Illustre vigne!

Son jet insigne

Pousse des rejetons fleuris:

Célébrer cet objet chéri,

N’est-ce pas célébrer Henry? (bis.)

Reflections from Henry Stoll

“Dans le cœur de Marie” is the fifth song in L’Éntrée du Roi, en sa capitale (1818), a one-act opéra comique by Juste Chanlatte, a Haitian man of letters who authored poems, treatises, songs, plays, and operas for the Kingdom of Haiti. In the opera’s third scene, Damis, performed by the playwright himself, pulls a song from his portfolio and presents it to L’Hotesse, adding “may it be to your liking!” Thanking him, L’Hotesse, played by Madame David, proceeds to sing. A paean to Queen Marie-Louise of Haiti, the song praises her “comely virtues” and “nobles attributes,” asking “To celebrate this cherished one / is it not to celebrate Henry?”

The melody is derived from “In diesen heil’gen Hallen,” an aria from Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (1791) and originally scored for bass. Chanlatte, however, refers to the tune as “Dans ce séjour tranquille” from Les mystères d’Isis (1801), a French adaptation of Die Zauberflöte by Bohemian composer Ludwig Wenzel Lachnith. It is in this adapted form that Mozart’s final opera was introduced to France and in which it was familiar to Chanlatte. Mozart’s music, however, was a rarity in early Haiti, eclipsed by that of French composers such as André Grétry, Nicolas Dalayrac, and Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny.

Quoi la trompette a résonné! …

Debout, magnanimes guerrières!

L’heure des combats a sonné …

Allons, volons à nos bannières: (bis.)

Voyez-vous flotter le signal?

Il part d’une Reine intrépide;

Déjà le cri d’un autre Alcide

Est jeté par le Général.

Aux armes ! braves Corps!

Aux accents de Marie

Combattons (bis.) pour le Trône,

Et vengeons la Patrie. (bis.)

Vive Marie et vive Henry

Restaurateurs du Nouveau Monde!

Vive le Général chéri

Sur lequel notre espoir se fonde! (bis.)

Vive le jeune Colonel

Qu’ont adopté les Amazones!

Que l’univers encense et prône

Son nom, son courage immortel!

Aux armes ! braves Corps!

Aux accents de Marie

Combattons (bis.) pour le Trône,

Et vengeons la Patrie. (bis.)

Reflections from Henry Stoll

“Quoi la trompette a résonné !” is by Juste Chanlatte, a Haitian man of letters who authored poems, treatises, songs, plays, and operas for the Kingdom of Haiti. In it, Chanlatte pays homage to Queen Marie-Louise and her guard of Amazons, a corps of sixty female warriors charged with the protection of the Queen and Princesses. According to a French consul to Haiti, the Amazons wore a tunic of blue silk, large satin trousers with gold or silver garters below the knee, and a gold and silver helmet with plumes of ostrich feathers. Each day, two Amazons stood guard at the palace for which they were armed with a lance and a bow and arrow.

The melody comes from the French national anthem or the Marseillaise, written in 1792 by Claude Joseph Rouget de L’isle and familiar to all members of the Haitian court. A spirited battle cry, Chanlatte’s refrain goes: “To Arms, braves Corps! / To the strains of Marie / Let us fight for the throne / And avenge the country!” The text proceeds to condemn the French—these “contemptible tyrants,” this “iniquitous race”—and urges the Amazons to strike down Haiti’s oppressors. The song ends triumphantly, exclaiming “Long live Marie and Henry / The Restorers of the New World.”

Melissa sings only the first and last verses in this recording, transcribed above.

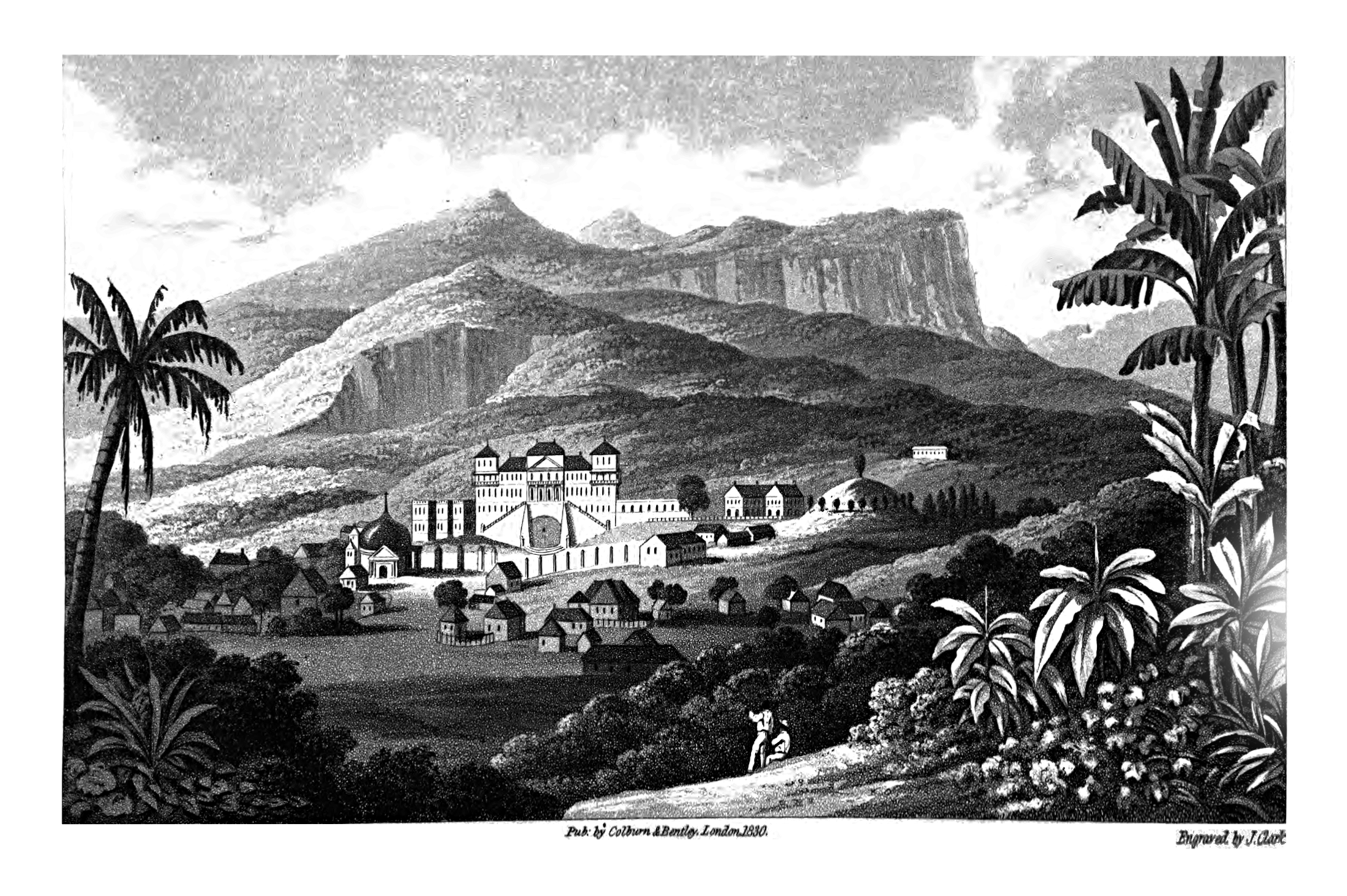

Spaces

There remain only a handful of artworks and engravings of Sans Souci palace, the principal royal residence of Henry and Marie-Louise Christophe, that show its structure intact prior to the earthquake that precipitated its destruction in 1842. Located in Milot, approximately 5 miles from the mountaintop fortress Citadelle Laferrière (Citadelle Henry), the palace was completed between 1811 and 1813. Though Sans Souci, like the Citadelle, became for some early chroniclers of Haitian history a symbol of Christophe’s ruthlessness and tyranny (an indeterminate number of labourers were conscripted to work on its construction), it serves as a monumental reminder of the lengths to which Christophe went to cultivate a spirit of refinement and sovereign pride for the nascent Black kingdom.

During Christophe’s reign, Sans Souci bore witness to a number of feasts and public celebrations and hosted a number of international dignitaries who later recalled the splendour of the palace in their memoirs and correspondence. One of the most widely publicised events to take place at Sans Souci was the ‘fête de la reine’: the 12-day feast held in honour of Queen Marie-Louise’s birthday that began on August 14 1816 recounted by Christophe’s ‘spin doctor’, Baron Pompée Valentin Vastey in his ‘Relation de la fête de … la Reine’. Though it is difficult to precisely determine Marie-Louise’s influence on Sans Souci from the ruined fragments that remain, and from the scattered documents that, owing to political upheavals after the fall of the kingdom, were subject to neglect and displacement, a handful of accounts remain that offer revealing snapshots. European newspaper accounts, for example, reveal that Marie-Louise made ‘large purchases … in Bremen, and other Hanseatic cities … of services for the table, brilliants, pearls, &c.’ which were paid for ‘in ready money, at high prices’. Similar accounts give detailed insights into court dresses manufactured in Europe for the queen and princesses. Beyond her influence on the material objects that contributed to the refinement of Sans Souci, historical accounts reveal that she also oversaw a ceremonial troop of all-female ‘Amazones’ who paraded on feast days.

This 1841 etching shows the front entrance to Playford Hall, as approached from the drive. Playford Hall was the Suffolk residence of the Clarkson family, and became a haven for Marie-Louise Christophe and her daughters after they fled Haiti for England in 1821. They stayed there for several months, passing the winter with the Clarksons, before settling in a house in Blackheath, Kent. The caption reads:

Playford Hall, Suffolk, the Residence of Thomas Clarkson Esq. M. A. One of the first and greatest Advocates for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

This Hall was the Seat of Thomas Felton, Bar. (Comptroller of the Household to Queen Anne;) whose sole Daughter & Heir Elizabeth married to John first Earl of Bristol, 1695. it is now the property of the Marquis of Bristol. it is said to have had four sides surrounding a Court-yard, with a Draw-bridge on the East & Gallery on the South:

Drawn Etched & Published by Henry Davy, Globe Street, Ipswich May 26, 1841.

This coloured print from 1822 shows the palace of Sans Souci two years after the fall of the Kingdom of Hayti. Beside Sans Souci to its left sits the church of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, which would have been a familiar vista to the Christophes and is identifiable by its distinctive duomo which has been restored on several occasions throughout its life-cycle. Despite the damage it has sustained in the last 200 years, the church had been one of the best preserved relics of the period of early Haitian sovereignty up until April 2020 when the church was engulfed by fire and the duomo was completely destroyed.

This was the last known English residence of Marie-Louise Christophe and her daughters. They lived at this address until September 1824, when they departed for Europe, never to return again to England. Their residency in Weymouth Street is confirmed in a letter that was sent by Marie-Louise to Catherine Clarkson shortly before her departure and in her last will and testament. The specific location of the address at number 30 (now number 49) is verified by an advertisement posted in the London papers for the sale of ‘Madame Christophe’s’ household property and also by the rate books for the Parish of St Marylebone for the period of 1824.

Built between 1789-1790 as part of the Portland Estate development, this Georgian townhouse remains largely unaltered, despite the substantial shelling to which the area was subjected during the Blitz.

Marie-Louise Christophe, together with her daughters, Améthisse and Athénaïre, stayed at this house for at least several weeks in October 1822. Listed in the Hastings Guide of 1822 as one of two holiday lets owned by a Mr Fagg (the second being the adjacent Exmouth House). Both houses were built as a speculation, the former being completed in 1821, several years after the completion of the latter in 1817. As such, Marie-Louise would’ve been among the first guests of the newly-built house in a fashionable, emerging seaside spa.

A letter sent to Catherine Clarkson by Athénaïre on 26 October 1822 offers a detailed account of this stay. During their stay, they were visited by the ‘demoiselles Thornton’, the daughters of the abolitionist Henry Thornton and later wards of Sir Robert Inglis, who recalled a journey to London from Hastings with one of the Christophe daughters in his 1840 travel diaries after a chance encounter with Marie-Louise in Pisa. The letter testifies that the women found the seaside climate of Hastings to be much milder and much more accommodating than at Blackheath, helping to alleviate the effects of Marie-Louise’s rheumatism.

The photograph shows the façade of the Villa Ducale, or Casa/Palazzo Bolongaro, once home to the writer and philosopher Antonio Rosmini and now home to the Centro Internazionale di Studi Rosminiani. Nestled on the shore of Lake Maggiore in Stresa, Piemonte, it was here that, in 1839, Marie-Louise Christophe sought solace at the invitation of Anna Maria Bolongaro after the sudden death of her daughter Athénaïre. Though little is known about the exact details of Athénaïre’s tragic and unexpected passing (anecdotal accounts suggest that she suffered a fall in the mountains), the parochial archives, held in the Chiesa Parrocchiale just adjacent to the villa, hold her sparse and incomplete death record. Anna Maria Bolongaro, widowed in 1818, established a reputation as a benefactor of the arts, education and the church (much like Marie-Louise). She welcomed many notable personages to her home, including Antonio Rosmini, who became a firm friend and later heir to the Villa Ducale.

It is in the letters of Gustavo Filippo Benso, Marquis of Cavour (province of Turin), who, like Anna Maria Bolongaro, was a close associate of Antonio Rosmini, that we learn of Marie-Louise’s sense of indebtedness to Anna-Maria. Writing to Rosmini from Turin in December 1839, he observed that:

’Quando veda in Stresa la Sig.a Bolongaro mi farebbe piacere dicendole chevedo ben sovente qui la disgraziata ex-regina di Haiti, che è vivamente compresa di riconoscenza verso questa Signora per le gentilezze e benefizi ricevutine quest’autunno … L’antica Regina di Haiti partendo dal Piemonte ove forse non, avrà occasionedi ritornare, m’incarica di fare pervenire a Madama Bolongaro i suoi riconoscenti saluti coll’assicurazione ch’essa non dimenticherà mai i benefizi ricevuti daquest’ottima signora; essa manda pure distinti complimenti all’Abate Branzini.’

’When I see Madam Bolongaro in Stresa, I would be pleased to tell her that I very often see the unfortunate ex-Queen of Haiti here, who is deeply grateful to this Lady for the kindnesses and benefits received from her this autumn … The former Queen of Haiti, leaving from Piemonte, where perhaps she will not have the opportunity to return, instructs me to send Madam Bolongaro her grateful greetings with the assurance that she will never forget the benefits received from this excellent lady; she also sends distinguished compliments to Abbot Branzini.’

Given the depth of Marie-Louise’s avowed gratitude towards Anna Maria Bolongaro, we might imagine that she found some comfort in the company of like-minded people at the Villa Ducale, despite the immensity of her loss.